An early simulation with PSC’s second supercomputer, the Cray Y-MP, showed that carbon fiber was a plausible replacement for increasingly rare Norway spruce in crafting string instruments.

CMU Project in 1988 Used PSC’s Cray Y-MP to Show Violin Top Plates of Carbon Perform Similarly to Norway Spruce

PSC40: Powering Discovery

2026 marks 40 years of PSC. As we continue on with cutting-edge innovation, we look back on four decades of history in computing, education, and groundbreaking research—and the people who made it happen.

When Europe’s forests began to decline in the 1980s, the Norway spruce that makes the best violin top plates became more scarce. Instrument makers started to experiment with carbon fiber as a top-plate material. In 1988, an acoustic scientist and violinist from Carnegie Mellon University used PSC’s second supercomputer, a CRAY Y-MP, to simulate vibrations in Norway spruce and carbon fiber top plates. He found that the new material’s acoustics were promising, helping to lead to today’s competitive carbon-fiber string instruments.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

Whether you’re chilling to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons or rocking with Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir, violins have a unique way of touching something deep inside human beings. Yeah, there’s that joke about the tiniest violin. But we wouldn’t have that joke if it weren’t for the fact that violins so powerfully trigger human emotion.

Imagine the horror of music lovers, then, when in the 1980s scientists discovered that Europe’s Norway spruce forests were dying off. Long considered the ideal wood to make the critical top plate of a violin, the trees suffered, as 20 to 25 percent of European forests experienced moderate to severe damage from pollution and natural stresses.

Some violin makers began experimenting with epoxy-bonded carbon fibers as top plates for violins. The question remained, though: Could these materials ever measure up to the ideal acoustic performance of Norway spruce?

CMU acoustic scientist and lifelong violinist Robert Schumacher decided to find out whether the relatively limited physical properties of carbon fiber could match the complex behavior of wood. His tool was a series of simulations on PSC’s second supercomputer, a Cray Y-MP.

HOW PSC HELPED

Norway spruce wood has unique physical properties. Violin makers for centuries had depended on testing the quality of samples by bending them both with and against the grain, and by twisting them. The idea was that the motions the wood could make gave a sense of how it would vibrate — its acoustics — when a violin’s strings were vibrating above it.

Problem number one: Carbon fiber doesn’t have a grain. Its properties are basically the same in all three dimensions, and so would fail such a test.

Modern theory had questioned that traditional approach, though. A flat piece of wood’s ability to vibrate depends on three elastic compliance elements. These are indeed shown by the wood’s ability to bend and twist in the way that the old masters tested. But a violin’s top plate is arched, which potentially changes everything.

Problem number two: Acoustic theory said that testing a curved surface would require nine elements, not just the three that violin makers tested.

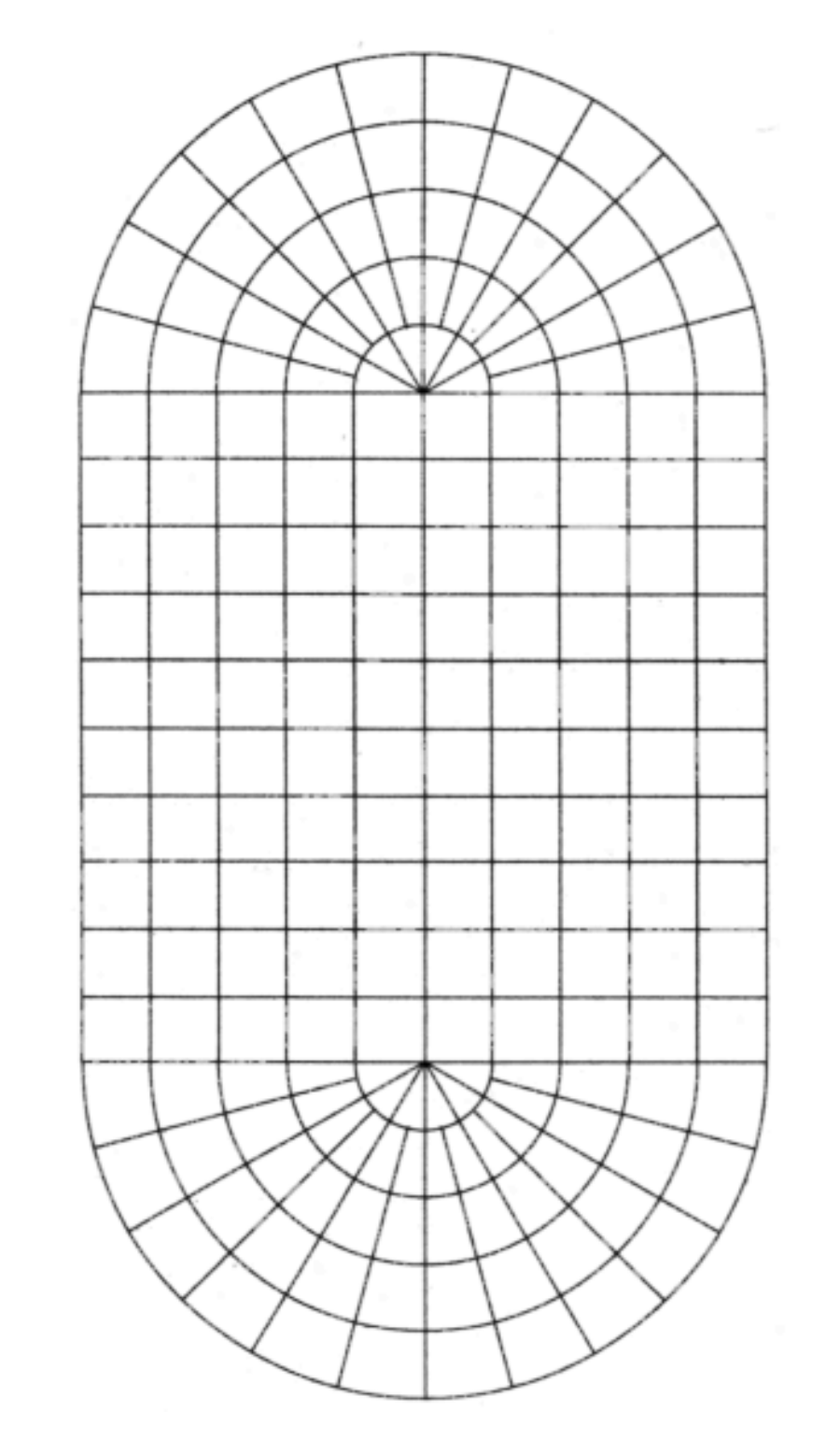

To clear up these contradictions, Schumacher created a simplified virtual top plate in the Y-MP. It was called the “stadium” model because it was an elongated oval, like a stadium. It allowed Schumacher to investigate how changing the arch altered the acoustics without the effects of the complicated cutouts and shape of a violin.

He would need to test a stadium model with over 200 elements and 1,000 nodes. Each top-plate configuration had to be tested 19 times to see how its curves changed how the plate would vibrate. The Y-MP made this possible, taking only five minutes per run to chart out how each top-plate’s shape would alter the nine elements.

The simulations shed light on both issues. First, it turned out that the old masters weren’t completely mistaken. The nine elements described a curved plate’s acoustics well. But as it turned out, using only the three traditional elements gave results that were only a few percent off.

The other surprise was that Norway spruce’s unique properties weren’t as important to making the material vibrate the right way as we might have thought. Running the stadium model again using the elastic compliance numbers of carbon fiber provided a good match to the natural wood, suggesting that the material could be used to make violins with the instrument’s characteristic sound. Schumacher reported his results in The Journal of the Acoustic Society of America in October 1988.

These days, carbon-fiber string instruments are common, even in professional orchestras. Yo-Yo Ma sometimes plays a carbon-fiber cello. It comes down, maybe, more to an individual musician’s taste and preferences than any straight-up difference in quality. Giving that choice to some of the world’s greatest string musicians began with a simplified oval shape tested on PSC’s second supercomputer.