A 3D rendering of the delicate components of a quantum computer.

Artificial Intelligence Improves Monte Carlo Simulations of Quantum Dots, Improving Accuracy of Storing and Reading Information

Quantum computers promise a giant leap forward in computing power — maybe. One reason we don’t know is that we haven’t made a quantum computer with enough qubits, the quantum equivalent of bits in a traditional computer, to tackle real-world problems. A team of researchers from PSC and the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in Brazil used a series of supercomputer simulations to reduce the uncertainty of obtaining information from quantum dots, showing that a system with as many as 30 electrons can be workable. The work also sheds light on several phenomena important to condensed matter and materials science research.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

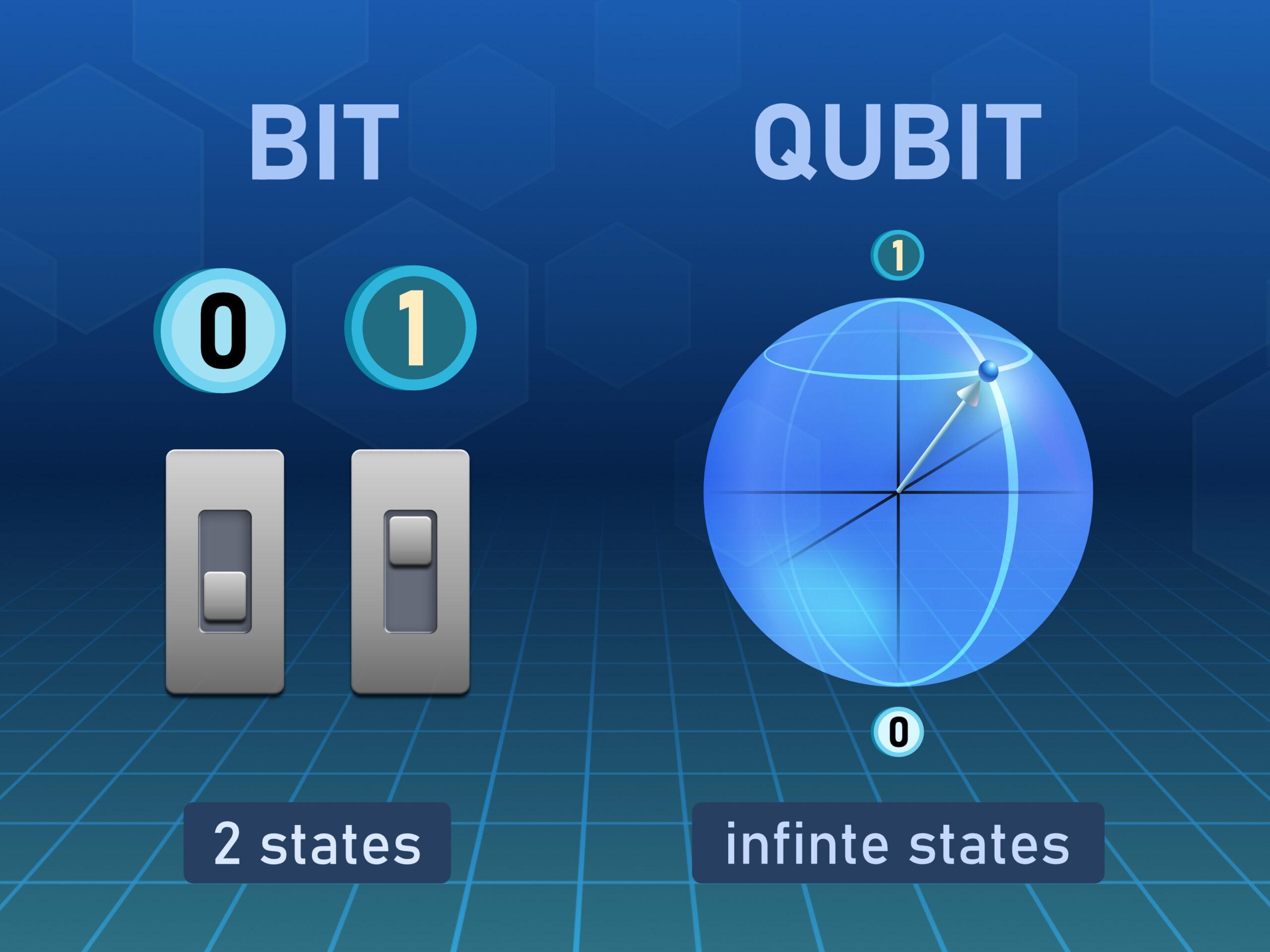

One of the biggest questions in advanced computing today is when we will have a true quantum computer — that is, a computer that calculates using the complex, shades-of-gray rules of quantum mechanics rather than the simple “on/off” switch of conventional computers. What will it be able to do that traditional electronic computers can’t? One roadblock to getting that quantum computer, though, is making it big enough to tackle real problems. A modern computer chip can store hundreds of billions or even trillions of one/zero “bits” of information. Today’s quantum computers, on the other hand, are based on only dozens of qubits, the quantum equivalent of a bit. Experts estimate that it’ll take about a million qubits to power a true quantum computer. Which is a tall order today.

The problem lies in the nature of qubits. In a traditional computer, you can store a 1 or a 0 in bits using transistors and electrical currents that are highly controllable. Qubits offer untold promise partly because they can process information via superposition and entanglement: They can be in any state between 1 and 0, offering resources and a complexity of stored information that are not available to a traditional computer. But because qubits are based on single or small numbers of particles, they obey the weird rules of quantum mechanics. Quantum particles interact with each other and their environment in ways that make both storing the information stably and reading it accurately very complicated.

Of course, qubits have to be made of something, and that’s another place where things get tricky. In order to have a true qubit, capable of storing the somewhere-between-one-and-zero information needed for a quantum computer, you need a physical device that is small enough to display quantum behavior. Too large, and it starts to behave by the classical rules that govern conventional computers.

Quantum dots are one approach to building qubits. A quantum dot consists of a small number of electrons trapped in a tiny space. Because of those small dimensions, they are tiny enough to display quantum behavior. As an added benefit, quantum dots can be created on semiconductor chips, as in traditional computers. That makes them relatively easy to manufacture, integrate into computing systems, and potentially scale up to usable sizes.

“Because I know the position and the velocity of a classical particle … I can predict where the particle is going to be at any time in the future, or in the past, right? In quantum physics, the way you predict what’s going to happen, it’s by knowing the wave function … I can’t predict exactly where the particle is going to be, but I can predict what’s the probability that it will be there [and what] the wave function is going to be like in a certain time in the future. So that’s why the wave function is so important. It’s the key. It brings all the information of the system.”

— Bruno Abreu, PSC

Scientists had discovered that they could begin to estimate the wave function of particles trapped in a quantum dot — read its somewhere-between-zero-and-one state — using a Monte Carlo method. Like a gambler playing roulette many times in a row, Monte Carlo simulations sample the state of a system repeatedly. The average answer you get tells you the likely state. The variation between the different simulations tell you how certain you can be in that answer.

Quantum behavior is about how small systems get blurry at the smallest sizes and energies. Because of that, we’d expect a qubit’s quantum behavior to be at its purest, and the answer to the calculation most accurate, when it’s at as low an energy state as possible. Scientists call that low-energy state the ground state. But here the Monte Carlo method often hits a roadblock. Because it depends on guessing the overall structure of the wave function at the outset, it suffers from the assumptions the humans make about the system. This affects the certainty of the answer.

PSC’s Deputy Scientific Director Bruno Abreu, with colleagues at UNICAMP, wondered whether an AI approach could improve on the Monte Carlo approach to quantum dots.

HOW PSC HELPED

The scientists used a type of AI called a neural network coupled to a Monte Carlo series of simulations. The AI learned as it made guesses, without human input. Because of that, it wasn’t beholden to any assumptions by the researchers. It could possibly break through the limitations of previous Monte Carlo methods.

Using the Delta supercomputer at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, the team trained their neural network in what amounted to a series of guesses. The steps decreased the energy, at first by a lot but then leveling out. When further steps didn’t improve the wave function, the sims had their final answer.

“What we’re showing in the paper is that through a neural network, you can … get rid of some of the biases. If I [give the Monte Carlo simulation an initial state] there’s some specifics … that are fixed … If I’m learning that through a neural network, I’m not giving this initial bias to the wave function … I’m just letting the neural network learn the shape of the wave function without me telling anything about it. So that’s the key difference here. It’s kind of like an unbiased presentation. And that equates to better accuracy.”

— Bruno Abreu, PSC

Over hundreds of thousands of such optimization steps, the simulations got the energy level lower than had been possible with the state-of-the-art non-AI Monte Carlo methods, indicating a better representation of the system’s wave function. The team reported their findings in the journal Physical Review B in October 2025.

These results pave the way to a better understanding and more precise description of usable quantum dots, which can become platforms for building qubits at scale. But they’re also applicable in a number of other fields where quantum behavior is important. These include understanding quantum behaviors of nuclear matter, ultracold gases, and condensed matter systems involved in discovering new useful materials. In the future, the team plans to study how their neural network Monte Carlo method can be scaled up to control larger numbers of particles, as well as to refine the method’s ability to predict quantum behavior. This includes potential quantum circuits running on quantum computers as part of the neural network.