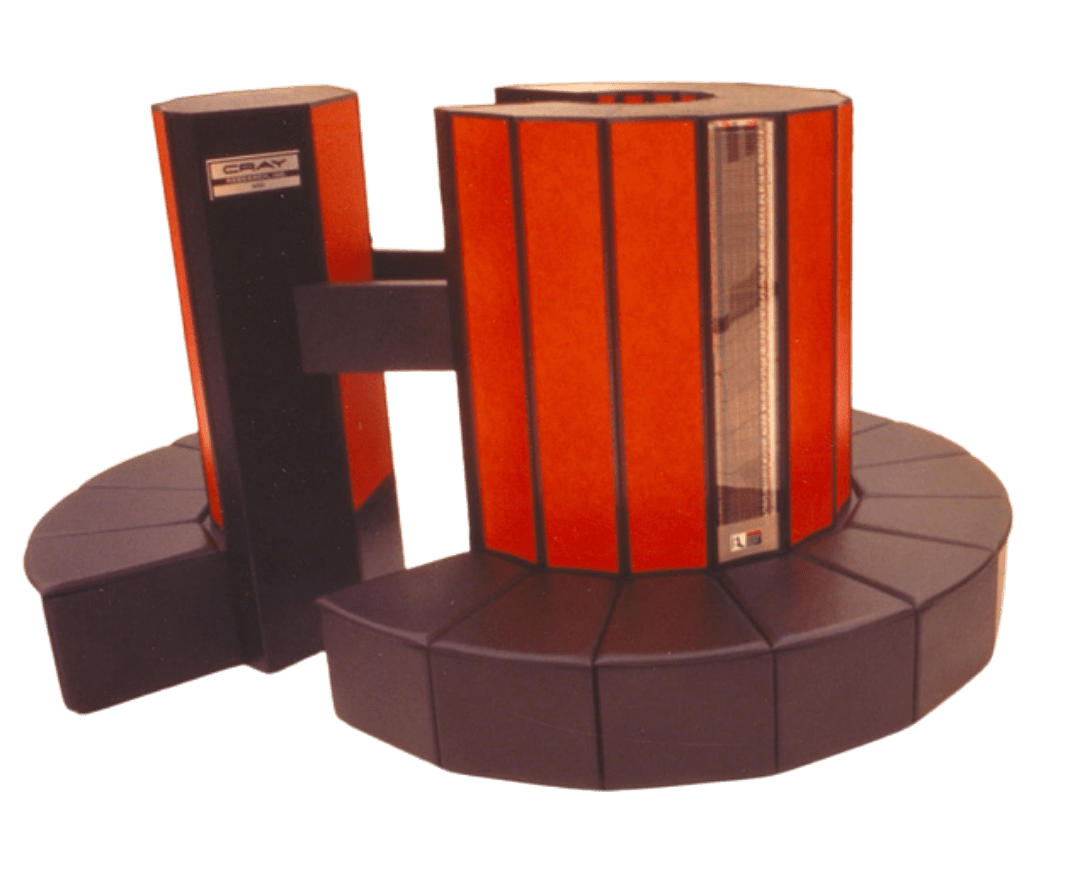

“Pop art”: The Pittsburgh-based Alcoa Corporation used the Cray X-MP supercomputer to design the beverage can we know today. Credit: Emily Voelker/PSC

1987 Alcoa Work with PSC Supercomputer Helped Set Stage for Industrial Supercomputing Design Revolution

PSC40: Powering Discovery

2026 marks 40 years of PSC. As we continue on with cutting-edge innovation, we look back on four decades of history in computing, education, and groundbreaking research—and the people who made it happen.

With 180 billion beverage cans transported and used each year, even a tiny decrease in weight can add up to big bucks saved. In 1987, a team from Alcoa used PSC’s Cray X-MP supercomputer in a project that was as seminal as it was iconic. For the first time, a PSC industrial affiliate used a high performance computer to show how shaving thickness off the walls of an aluminum can would affect the can’s ability to preserve its contents — and avoid damage that would cause consumers to choose another can.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

One ten-thousandths of an ounce — give or take — doesn’t seem like much. Certainly, if you lifted a 12-ounce beverage can, you couldn’t tell the difference. But multiply that by the staggering 180 billion beverage cans used every year, it comes to over a million pounds. Think of the energy and materials cost to make those cans. To ship them. To handle them through the machinery that fills them with beverages. To cool them and their contents to the frosty temperatures we like.

It adds up.

So we can see why, in the 1980s and even today, aluminum can producers like Alcoa, and their customers, were obsessed with shaving the tiniest bit of weight off each can. Between 1979 and 1987, the industry had reduced the thickness of the walls of their cans by about three thousandths of an inch. Not much per can. But big money, taken all together.

It wasn’t simple, though. If you reduce the thickness of a can’s walls, it becomes more fragile. More likely to dent with handling. More likely to deform if the temperature changes. More likely to burst open. And consumers will reach past a dented can to pick an undamaged one. Even a can with a minor dent that doesn’t affect the quality of the contents. That kind of waste can eat up any savings in the weight of the can.

In 1987, Andrew Trageser and Robert Dick of Alcoa Laboratories had hit a wall. Using the best mainframe computers of the day, the VAX 8650 and 8800, they’d pushed to the limit their ability to cut design costs by working through problems on the computer before trying designs in real aluminum. The problem was that the power of those computers limited them essentially to simulating the cans in only two dimensions — a cross-section of the can. The scientists could swing their two-dimensional model around 180 degrees to get the full can. But that only worked for dents and deformations that were symmetrical.

That year, Alcoa took the step of becoming PSC’s first industrial affiliate. By partnering in this way with the supercomputing center, the company’s laboratories gained access to PSC’s first supercomputer, the Cray X-MP.

HOW PSC HELPED

Today we tend to compare PSC’s first machine with a smartphone, which has more computing power — and is vastly more user-friendly! But it’s easy to forget what a wonder the X-MP was in its day. It could tackle problems that had been impossible to solve just five years earlier, and opened windows that scientists are still, profitably, looking through today.

The Cray had, for the time, blistering performance at the task of simulating the cans in 3D. Its greatest strength was that, unlike its predecessors, it could perform computations in parallel, with four processors sharing data from the same memory. Parallel processing breaks down complex problems into pieces that can be solved at the same time instead of one after the other. Today’s supercomputers do it at the programming level; the X-MP was an earlier version of parallel processing that worked at the level of the computer’s system.

The Cray X-MP opened up the Alcoa team’s ability to simulate new modes of failure for the cans. For the first time, they were able to simulate how increasing pressure inside the can would deform it. These simulations matched later real-world tests exactly. Also for the first time, the team was able to simulate the messy situation when a can falls to the floor. The supercomputer now let them simulate impact stresses, how the can’s aluminum walls would deform, and how shaving a little more off of their thickness would change things. One major innovation the Alcoa team came up with was making the cans concave at the bottom, to improve the can’s pressure management.

Alcoa also began using an approach called Monte Carlo modeling. Instead of simulating only one event, they’d use the Cray’s speed to simulate many events with tiny, random differences between them. That gave them a far better understanding of the range of effects that could happen in the real world rather than just one idealized drop.

Writ larger, Alcoa’s experience working with PSC led to a new era in which the largest companies invested in their own supercomputers. Today, PSC’s industrial partnerships are focused more on the small- to mid-sized companies that can’t invest $20 million (or more!) for hardware and operations. Companies that are interested in becoming PSC industrial affiliates today can find more information by emailing corp-relations@psc.edu.