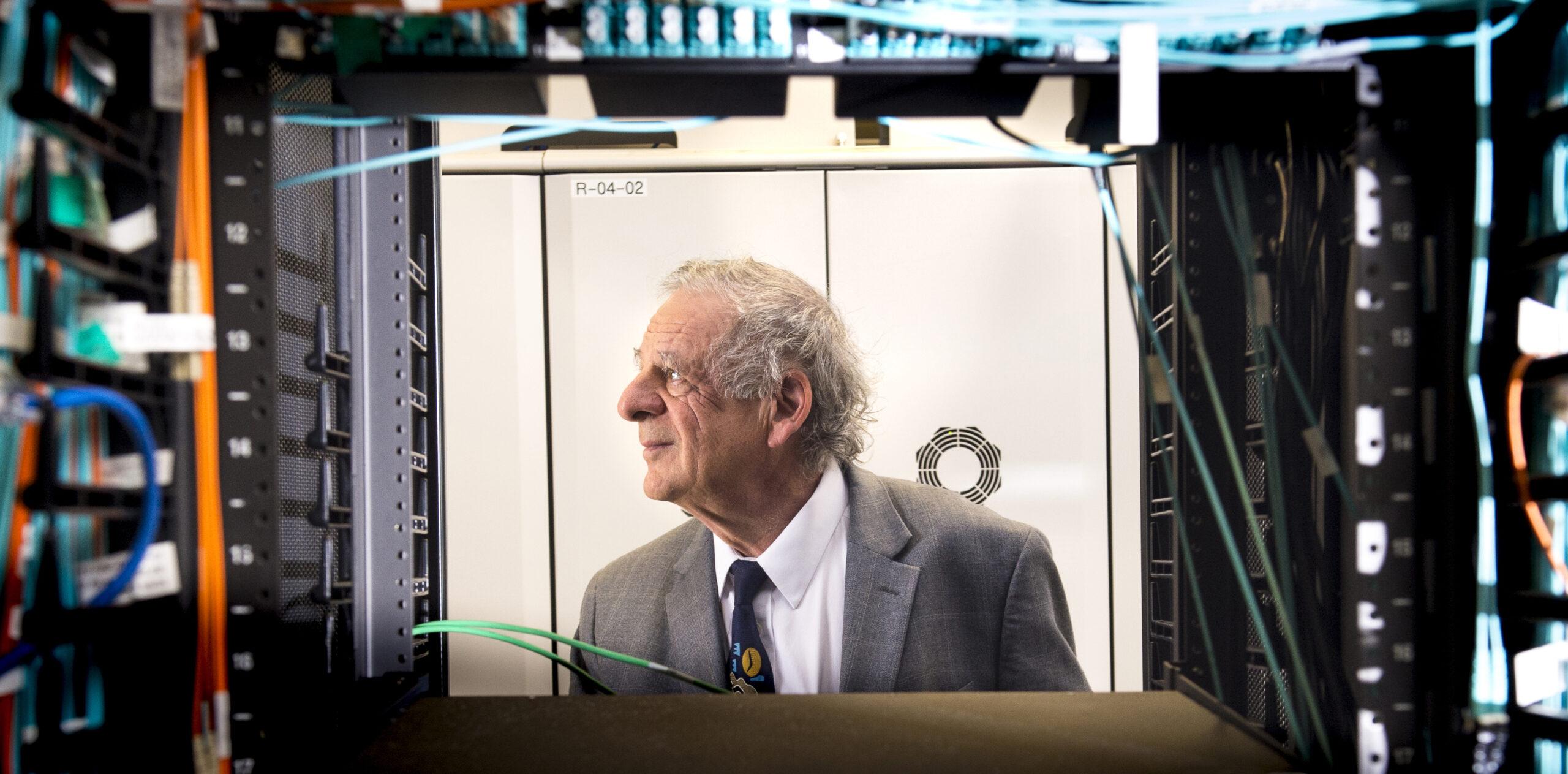

Ralph Roskies, PSC founder and co-director. Photo credit: Tom Altany/University of Pittsburgh

PSC’s Chris Csonka sat down with PSC co-founder Ralph Roskies to talk about his early days at PSC, its founding, and how he collaborated with Mike Levine and Jim Kasdorf

PSC40: Powering Discovery

2026 marks 40 years of PSC. As we continue on with cutting-edge innovation, we look back on four decades of history in computing, education, and groundbreaking research—and the people who made it happen.

WORKING TOGETHER

CC You and Mike Levine had worked together prior to PSC. You were both in the same field, physics. Can you talk a little about that?

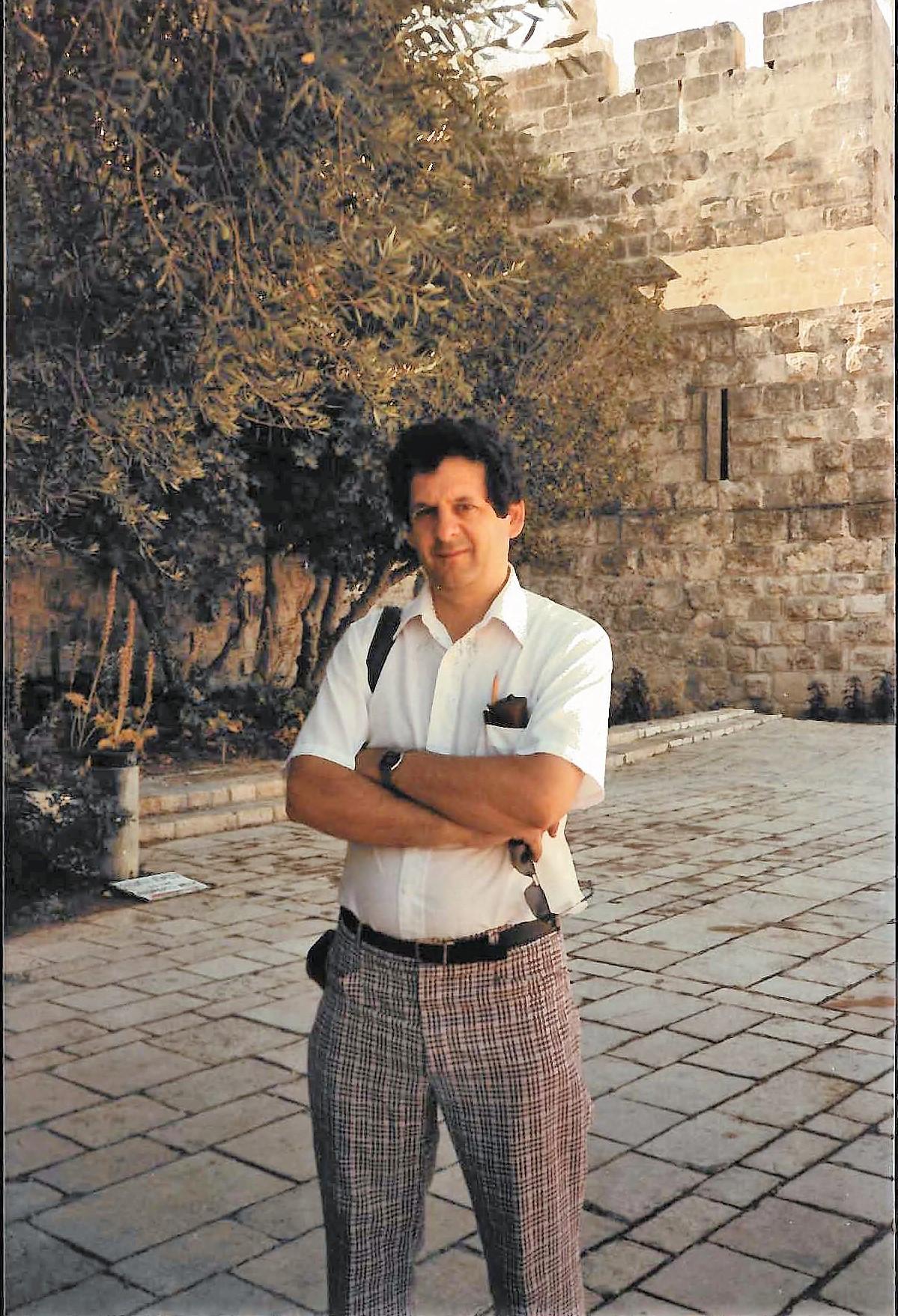

RR I was intrigued by the ability of computers to do algebra. I knew they could do arithmetic, but I was working on a topic that required a lot of algebraic manipulation. There’s nothing deep and profound about it, but you can make mistakes easily. If you could train a computer to do this, presumably you could reduce that. I came across work that Michael had done in building a language for algebraic manipulation on computers. When I came to the University of Pittsburgh, I sought him out so I could use these tools.

That’s how it got started. Michael was already at CMU and then I got an offer from Pitt. When I realized that he was nearby, I said, let’s get together. That’s how we started to collaborate. We started PSC because we felt that Pitt and Carnegie Mellon didn’t have enough computing power for the kinds of problems we were trying to solve.

We complained to the universities, asking for better equipment, and guess what? They put us on committees to study the problem! I was on a committee at Pitt, Michael was on one at Carnegie Mellon, what to do about inadequate computing power. The National Science Foundation (NSF) had just issued a new solicitation, they were asking for proposals.

CC To get a grant for this type of work?

“The NSF said, supercomputing is becoming important, but supercomputers are not available at universities, industry has them. This is bad because people are not being trained in their use.”

RR Exactly, the timing was perfect for us. We put out a solicitation for people to describe what they would do, from a scientific perspective, if they had access to more powerful computing. The implication being that we would provide the money to buy a supercomputer. While the timing was right, there were other universities already in the market for this. These were our competitors.

We’d been asking the universities to give us money for equipment, thousands, even tens of thousands of dollars. We needed millions of dollars. That’s what a supercomputer cost in those days. Mike said to me, “Have you seen the proposal? Don’t you think we should respond?” I said, “Are you crazy? We can’t even get $10,000. Who’s going to give us a million dollars?” He looked at me and said, “Who else should they give it to?”

CC What great framing!

RR It’s easy to say I’m not worthy, but much harder to say, oh, he’s more worthy than I.

“Mike Levine said to me, ‘Have you seen the proposal? Don’t you think we should respond?’ I said, ‘Are you crazy? We can’t even get $10,000. Who’s going to give us a million dollars?’

“He looked at me and said, ‘Who else should they give it to?'”

PSC COMPETITORS

CC You mentioned competitors. At the time, were there only so many of these systems available? Were you, literally, competing with other schools and institutions?

RR Oh, yes. The obvious competitors were University of Illinois, [UC] San Diego was there, Cornell was another one. We knew that we would have stiff competition. That’s who we were worried about. We put together a good proposal, then we asked folks at Pitt, what new science could they do with access to these kinds of supercomputers? We got all sorts of answers.

I should add something else here. I asked Michael, why would anybody believe us? Neither of us had run a supercomputing center or had direct experience with them. Before we started this whole effort, I had made contact with the guy in charge of supercomputers at Westinghouse, Jim Kasdorf.

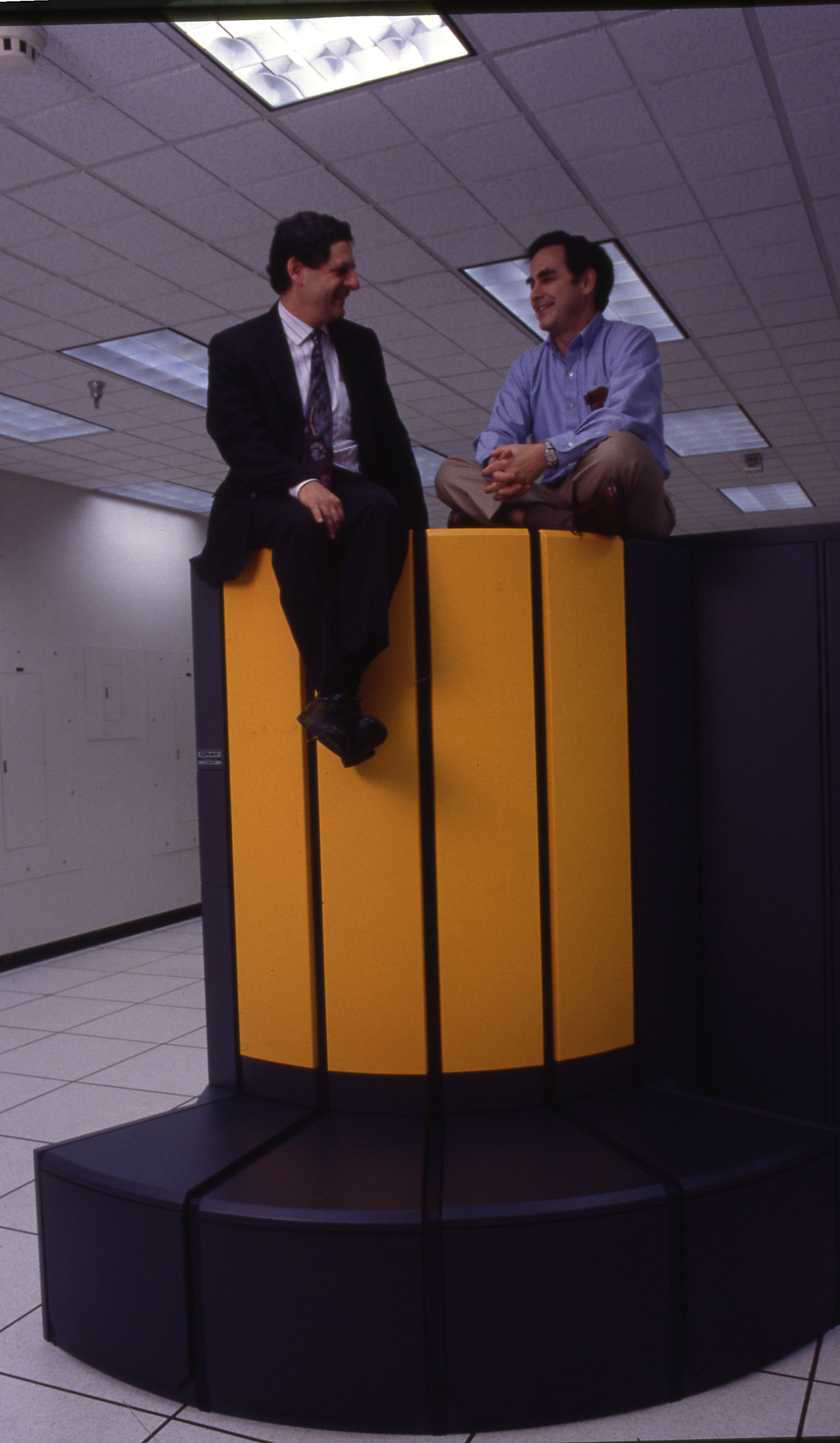

THE TRIUMVIRATE

RR I told Mike, we should bring in Kasdorf because he had experience using these systems. Then nobody can say, these guys don’t know what they’re doing. So, I called Jim and he was eager to join this thing. That’s how we made the triumvirate. Jim lent the managerial experience of using these big systems, Mike and I brought the scientific knowledge.

That’s how it all started. Jim, Michael, and I are all good at writing. Kasdorf particularly. We ended up writing a good proposal. I think we were, I know I was, surprised that we won it. I was thrilled! We spent a lot of effort writing about the kind of science we could do, about the people at our institutions who could contribute. But, we didn’t put anything in about the administration, who was going to be in charge. We were very naive about these things.

There were three of us writing this proposal. Maybe, to NSF, Kasdorf was of secondary importance because he was at Westinghouse and not at one of the universities. But we didn’t say anything about how we would organize this thing. And then NSF sent somebody and we had to make an oral presentation defending what we were doing. It was a big enough deal that the provosts of the universities attended this meeting.

“This guy from NSF said to us, ‘Who’s going to run this thing?’ The CMU provost, Angel Jordan, said, ‘Ralph and Mike are going to run it.’

“And my first thought was, ‘What?!’ I mean, I had the presence of mind NOT to say it aloud, but that’s what I was thinking.”

RR So that’s how it was organized. It was a proposal sent in by Pitt, CMU, and Westinghouse and Michael and I were the two co-directors. By the way, it was a co-directorship so that the two universities felt that they’re both collaborating on it and not one running it and the other just “tagging along.”

Later, we found out this raised questions at the NSF. They prefer to have one person in charge that they can approach if they don’t like what they’re seeing. But we managed to do it. And it was a particularly good collaboration. Jim had all that experience already. And I had closer ties to the scientists at the university than I think Michael did at Carnegie Mellon.

Michael was more knowledgeable about the hardware than I was, I think even more so than Jim. That’s the way it worked out, from my point of view. I was more the person that worked with the users. Michael and Jim understood the supercomputer hardware. So that’s how you divide it up. I knew a lot about computers, but I knew about laptops and things like that, not supercomputers.

CC Talk more about Jim Kasdorf’s contribution.

RR His role was not managing people at PSC. But he was involved all the time. You know, every few years we had to replace the computers. Jim was very involved in that sort of thing.

CC I see. Procuring new systems and helping write proposals?

RR He was a good proposal writer. And when we started, we didn’t know much about supercomputers, but he did. In addition, he knew all the people who were important. We were just newbies, so he played a key role in that way.

CC Yes, that can make a big difference, having the “in,” as they say.

RR But that’s why it was such a good proposal. I had to talk Michael into accepting Jim: He was worried about bringing industry in and whether his staff would like that. Anyway, I prevailed and it was a really good thing.

CHALLENGES

CC Yes, it seems like it turned out that way. Over your 30+ years at PSC, what would you consider your greatest challenge?

RR The first challenge was winning that initial proposal! We worked like hell on it. I mean, we really put in a lot of effort. One of the greatest challenges was, how do you build a staff, integrate them, and make them feel important? I never ran any big effort where people reported to me as a group before. And neither had Michael. So that was our biggest challenge, just building a cohesive staff, integrating them. And we managed to do this.

CC PSC is the kind of place where people start as students or early in their careers, and they just stay. I would say the model you built worked well.

CC What was the hardest thing for you at PSC?

RR Replacing staff. I mean, I’ve never had people working for me and the idea that, you know, this guy was going to lose his job. It’s difficult to deal with.

“Well, I’ll tell you something interesting. You know Dave Moses?

He had a prominent position at PSC [Executive Director]. Well, he once told me, ‘You’re the best boss I’ve ever had.’

“And I said, ‘Why do you say that?’ And he replied, ‘Because you listened to me.’

“And I thought to myself and said, ‘What were you expecting me to do? I’m asking for your advice on things, of course I’m going to listen to you.’ Evidently, people felt that the [leadership] style we had was one where, those PSC guys, they’re really paying attention to what people tell them.”

POINTS OF PRIDE

CC Looking back over your PSC career, what would you say is your proudest moment?

RR Well, I’ll give you a specific example, but overall, I’m most proud that we built this organization and it was highly successful. One incident that really comes to mind relates to XSEDE (Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment), the precursor to ACCESS. There was an XSEDE meeting, and one of the speakers said, “You know, if some user wants access to supercomputing time and they don’t know what to do, all they have to do is dial 1-800-RALPH, and he’ll help them.” I thought, oh my God, I felt so good about that comment. That was one of my proudest moments.

CC When people talk about HPC centers, they all have valuable resources and people. But there’s a perception that when people reach out to PSC for help, they’ll get that help. PSC’s reputation for this seems to be unmatched. If you could change anything about your career, what would it be?

RR In retrospect, I should have spent more time understanding the hardware. I understood what kind of problems people were solving, but I depended completely upon Michael and Jim when it came to hardware. I should have spent more time on that myself.

FINAL THOUGHTS

CC What is something about you that people might not know?

RR I grew up in Montreal. There, you learn to skate as soon as you learn to walk. I loved hockey, but I was never good enough to make the school team. I was eager enough to play. Then, after I left Pitt and PSC, I taught at other places. And when I was at Princeton, they had a hockey team, but they let the faculty play as well as the students. These guys were not great skaters, so I could make this team. I played hockey when I was 66 years old!

RR Another thing, some people certainly knew about me, but I was a pretty good pianist. I once soloed with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra and the Beethoven Piano Concerto. That was the apex of my piano career.

CC Do you have a recording of that? No? Anything else that you would like to share about your time at PSC?

RR Well, I’m looking at my notes… One more thing, it’s a bit obvious, but PSC took a lot of time. I also spent a lot of time with my family. So, the fact that my wife and kids were so supportive, that made it all possible.

CC After you left PSC, did you retire or take up a different challenge?

RR When I left PSC, the provost at Pitt, asked me to take over the Center for Research Computing at Pitt. It’s not a national thing, but it’s a local Research center at Pitt. And after a brief time there, then, I finally retired.