Pitt Team Uses Bridges-2 to Build Automated, Open-Source Toolbox, Enabling Conservation Scientists to Survey Much Larger Regions with Limited Staffing

We live in a time when so many species are dying off — and due to our activity — that some scientists want to call it the Anthropocene, or “human dominated era.” To stem these losses, we first need to understand what’s out there. A team from the University of Pittsburgh used PSC’s Bridges-2 system to develop a software toolbox called OpenSoundscape that pairs artificial intelligence (AI) with other methods to identify the sounds made by wildlife species from the riot of noise in natural environments. This new toolbox enables automated detection of species from microphones placed in the wild, easing the workload of a limited number of scientists.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

In 2019, a software tool picked out a tiny song from the deafening chorus of a Panamanian rainforest. The software — called “ribbit,” of course — automatically classified the sound as that of the variable harlequin frog, which many biologists thought was extinct in that region. In 2022, ribbit identified the same song again. In 2023, scientists got visual confirmation; the frogs had returned after a mass die-off, a win in the conservation of the species.

At least 0.01% to 0.1% of species become extinct each year, a whopping 200 to 2,000 life forms gone forever. This rate is much higher than before our species took over the globe. Some scientists classify our era as the Anthropocene — a mass die-off on par with the K-T Extinction that wiped out the non-bird dinosaurs (among many more species).

With so many valuable drugs and engineering insights coming from nature, we literally don’t know what we’re losing. Species have value in themselves as well. Many conservation scientists would like to lessen our impact on the natural world and restore healthy environments. But to do this, we first have to understand what is and isn’t out there, where, and what time of year.

“It’s time-consuming to survey wildlife with people. Professional scientists are limited in the time they can spend in the field. Although more numerous, citizen scientists very rightly have preferences on where they’d like to go and what they’d like to look for, leaving out large areas, seasons, and many types of species. We think that automated sensors are the future of large-scale biodiversity data collection in the field.” — Justin Kitzes, University of Pittsburgh

Human experts are the gold standard for such surveys. But there simply aren’t enough of them to go around. Citizen scientists, volunteer enthusiasts, can help a lot — but they’re guided by their interests and tend to live in developed parts of the world, and so their findings don’t fully cover the globe.

So scientists have begun to turn to automated systems. Cameras and microphones can collect a wealth of data without humans having to be there. But you still need to analyze and identify. Again, not enough experts, not enough time. To help their own audio-based research as well as those of their colleagues, a team led by Pitt’s Justin Kitzes has developed a package in the Python programming language called OpenSoundscape. To develop this toolbox, they used PSC’s NSF-funded Bridges-2 supercomputer.

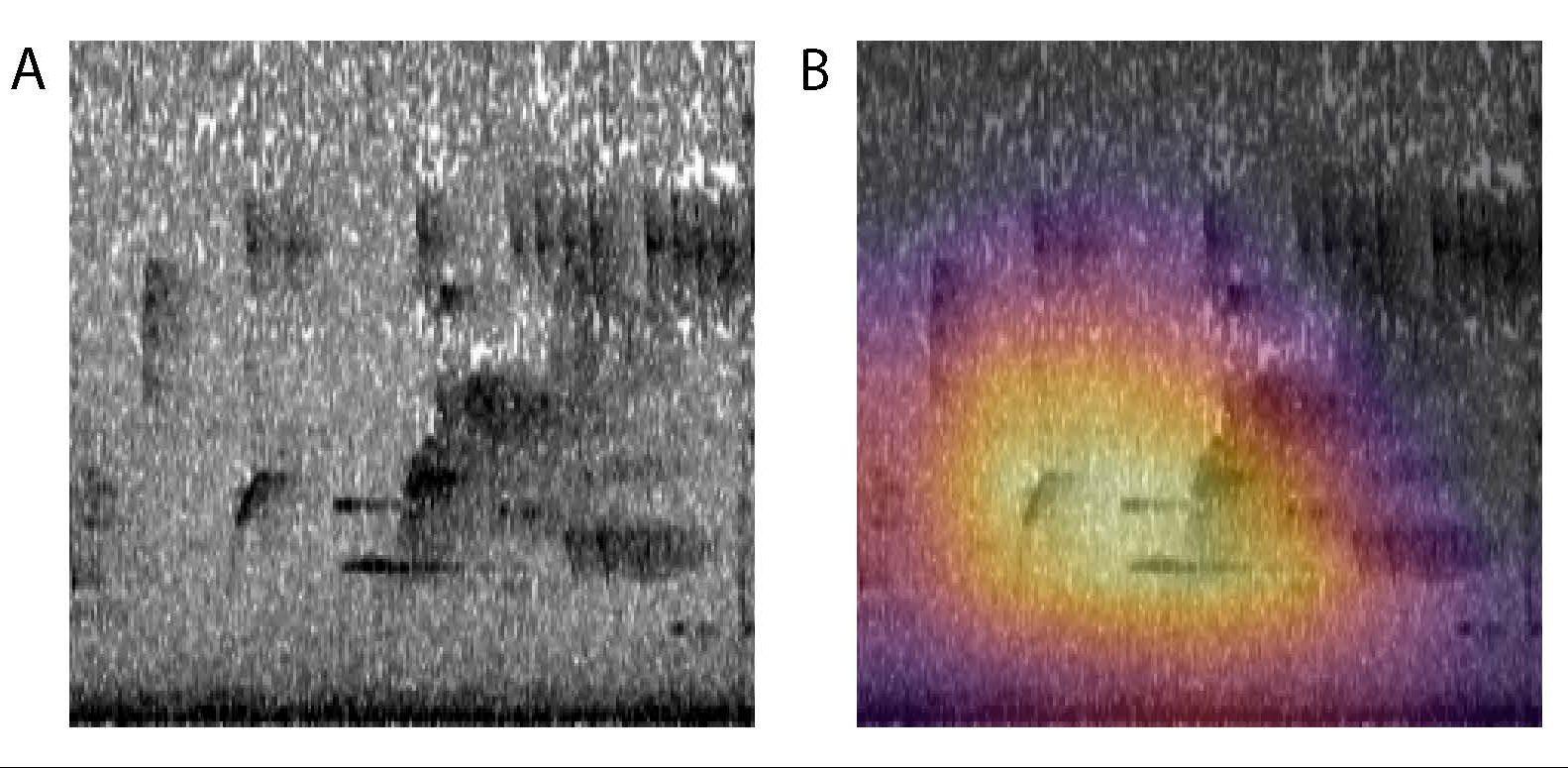

While the spectrogram of three seconds of audio of a forest environment is hard for humans to understand (a), the Pitt team’s CNN trained with OpenSoundscape recognized the song of an Eastern Towhee in the sample (highlighted, b).

HOW PSC HELPED

The Pitt group had ambitious goals. They wanted their tool to include convolutional neural networks. CNNs, a type of AI patterned after an early theory of how real brains work, could learn how to recognize animal sounds by trial-and-error. They do this using a training data set in which the “right answers” have been labeled by humans. On the other hand, some types of sound identification are best done by non-AI approaches such as ribbit. So they wanted ribbit, which they had developed, to be folded in as an alternative to CNN analysis. In addition, when multiple microphones are present, you can use the time of arrival of each sound to pinpoint where the creature of interest was. So that needed to be in there too. And it all had to be in a package that a biologist who doesn’t know AI and programming skills could learn to use quickly!

CNNs aren’t designed to identify sounds. But they’re great, powered by pattern-recognizing graphics processing units (GPUs), at identifying pictures. So the first step was to convert the audio recordings to spectrograms. These are images that display the characteristics of a soundscape in two dimensions — time and frequency. Spectrograms turn sounds into pictures that a CNN can recognize and work with. By scanning the complex spectrogram of a forest’s sounds for the tell-tale shape of a given species’ voice, the CNN could identify whether that species was present.

“We use OpenSoundscape on Bridges-2 for many of our projects. Bridges-2 is very fast and lets us do iterative development that’s hard to do elsewhere, because we can get quick allocations of really powerful GPUs. It’s been pretty critical to our work to have that capability. The support team has also been extremely helpful.” — Justin Kitzes, University of Pittsburgh

Bridges-2 brought powerful, late-model GPUs to the game, and plenty of them, as well as powerful number-crunching central processing units (CPUs) for parts of the computation that needed math. Particularly important was Bridges-2’s I/O, its ability to handle massive “input/output” of data to avoid traffic jams that slow the computation.

The team published their results in Methods in Ecology and Evolution in August 2023, including tutorials to allow other scientists to use OpenSoundscape as well as adapt it for their own use at no charge. To date, their own use of OpenSoundscape and the tools within it includes the recent identification of the variable harlequin frog in Panama, as well as training a CNN to identify the calls of several bird species of conservation concern in Pennsylvania as part of a larger, multi-group project funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The project aims to restore the environments these species need to survive.