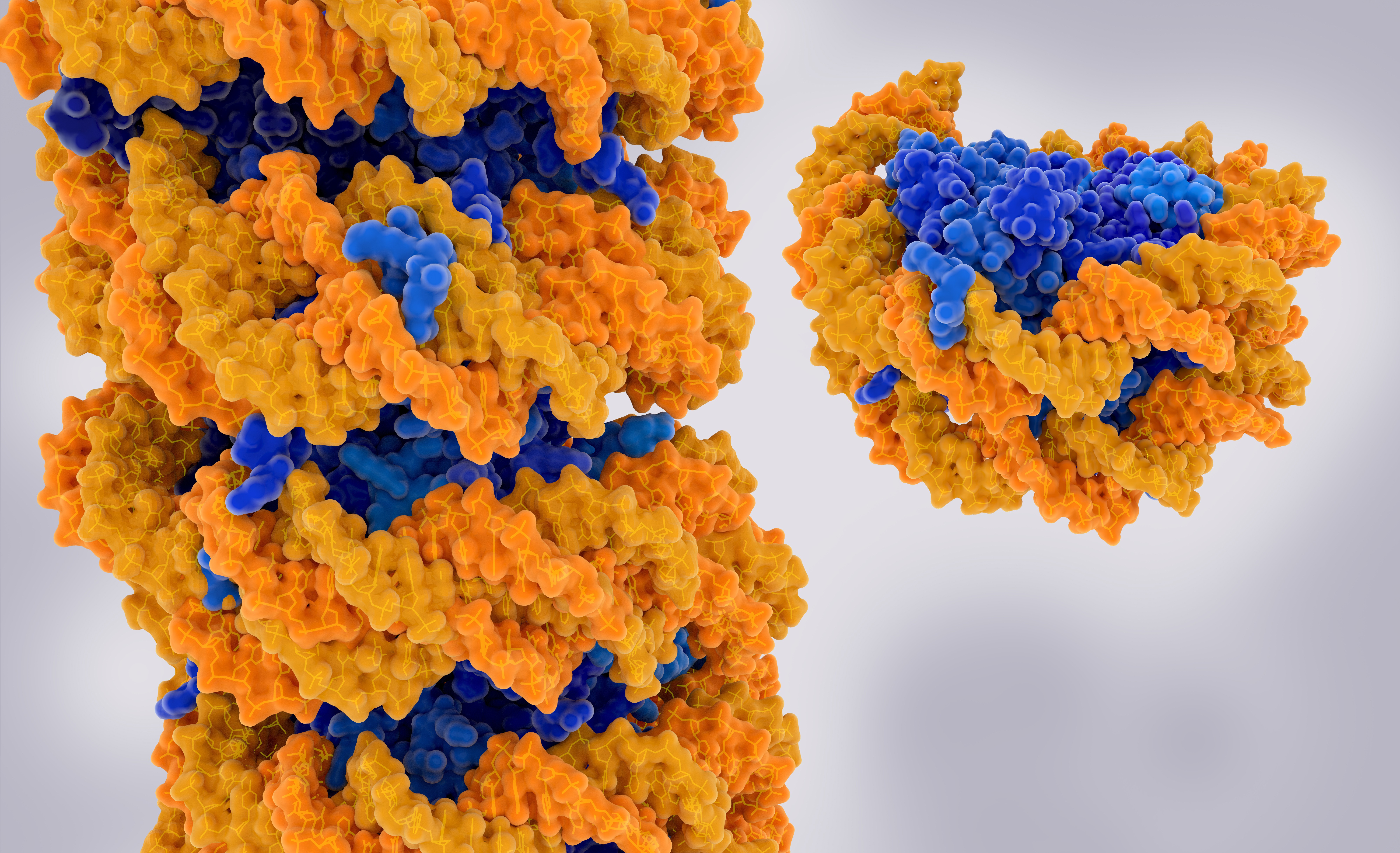

DNA strand wrapped around a series of protein-based nucleosomes (left) and an isolated nucleosome (right). DNA is orange, protein blue. Adobe stock.

Simulations on Anton at PSC Suggest Cancer Mutations in Nucleosomes May Affect DNA Accessibility

In our cells, over six feet of double-stranded DNA have to be compressed to fit in a space only a few thousandths of an inch across. The cell compacts its DNA using nucleosomes, protein cylinders that first wrap the DNA around themselves and then wind the DNA around them like a necklace. A team from the City University of New York (CUNY) used a second-generation Anton supercomputer developed by D. E. Shaw Research (DESRES) and hosted at PSC to simulate how cancer-causing mutations can destabilize nucleosome structure, possibly increasing gene accessibility, which may affect cancer progression.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT

Our DNA is the blueprint for our bodies. Every function of our cells and organs, in health and sickness, depends on the instructions of the genes encoded in the DNA being read loud and clear by the proteins and other molecules that make things happen.

Since almost every cell in our bodies has a complete copy of that blueprint, it’s also important that the genes that direct what a healthy body needs at a given moment are read — and only those genes are read. When some genes are overexpressed or repressed, diseases like cancer can develop.

Our cells face another challenge, but one that helps them control such gene expression. The DNA in our genomes, if it were stretched out in one line, would be over 2 meters long — six feet, six inches! That’s a tall order to fit into a cell that’s only about 3 thousandths of an inch wide.

The cell partly answers both of those questions with structures called nucleosomes. Tiny cylinders made up of the protein histone, and measuring about 11 nanometers across (0.4 millionths of an inch), nucleosomes help condense the DNA strand by wrapping the DNA around themselves, and then by linking with each other in a kind of braid.

“So what are nucleosomes? It’s the basic unit to store or package DNA … Because the DNA is negatively charged … it wraps around positively charged proteins [in the nucleosome] … But in order for your cell to do many important things … the DNA needs to unwrap, so also it needs to be accessed …”

— Sharon Loverde, CUNY

In addition to helping package the DNA, nucleosomes also help regulate which genes are more accessible. When a gene’s DNA is tightly packed up by the nucleosomes, the cell machinery can’t easily reach it, and it stays silent. If the nucleosome unwraps a bit and exposes the DNA, it can be more easily activated.

Augustine Onyema, a graduate student working with Sharon Loverde, professor of chemistry at CUNY, wanted to know how cancer-causing mutations in the histone protein affect the structure of the nucleosomes. These effects might contribute to activating genes cancer cells use to grow uncontrollably, and so represent a possible target for new drug therapies.

To better understand how these mutations affect nucleosomes, Onyema, Loverde, and colleagues elsewhere at CUNY turned to a combination of molecular dynamics simulations and laboratory work. Onyema carried out those sims using Anton, a special-purpose supercomputer for such simulations that was designed and constructed by D. E. Shaw Research (DESRES). The second-generation Anton machine they used was made available to scientists without cost by DESRES, and was hosted at PSC with operational funding support by the National Institutes of Health. (DESRES recently replaced that machine with a third-generation Anton, which also receives operational funding from the NIH.)

HOW PSC HELPED

The histone proteins and the nucleosomes they form are very large. Having to simulate so many atoms in multiple proteins and nucleic acids requires a lot of computational power. Also, the computer would need a relatively long simulated time for the mutations’ effects to become clear — on the order of microseconds. That’s shorter than an eyeblink in normal life, but for molecular interactions it’s an eternity. Plus, Onyema would need to repeat the sims three times, so he could compare two different mutations with the unmutated nucleosome.

This task would require a uniquely powerful supercomputer — one capable of producing long, detailed simulations. The second-generation Anton at PSC specialized in simulating the behavior of large numbers of atoms in complex protein molecules, and could do so roughly 10 times faster than general-purpose supercomputers.

“When I started this work, I … went ahead to run first the minimization equilibration … I had to use two GPUs to do that run with multiple CPUs, and just to get a 100-nanosecond [simulation] took about 21 days … So it therefore means, if we go by time, and based on calculations for my computer, [the actual simulations] might likely take a year … Anton was able to do all this within 2 days.”

— Augustine Onyema, CUNY

The 36 microseconds of Anton simulations that Onyema conducted showed that the two mutations — called H2BE76K and H4R92T — did disrupt the nucleosomes. By breaking salt bridges, formed when positively charged and negatively charged amino acids in the proteins link up, the mutations destabilize the normal interaction of the H2B and H4 histone proteins. The simulation results directed lab experiments by colleagues at CUNY, including previous graduate student Christopher DiForte working with CUNY professor Sébastien Poget. These lab experiments confirmed that the simulated protein was acting the way it does in the real world, which gives the scientists confidence that the simulation’s other predictions will be accurate. The team reported these results in the Biophysical Journal in July 2025.

The CUNY scientists have only begun dissecting the behavior of nucleosomes and cancer-causing genes in the histone proteins. One big question is whether the unstable nucleosomes allow the cell machinery to get to genes that normally would be silent as expected, helping to activate them in a way that serves the cancer cells’ uncontrolled growth. One interesting discovery that they’re following up on is that the destabilization may make genes more or possibly even less active, by regulating the dynamics and the stability of DNA wrapping around the nucleosome. This may impact the compaction of chromatin, leading to increased or decreased gene expression.